Biography

From his first music lesson to his legendary scores for David Attenborough’s BBC documentaries, explore George Fenton’s biography below.

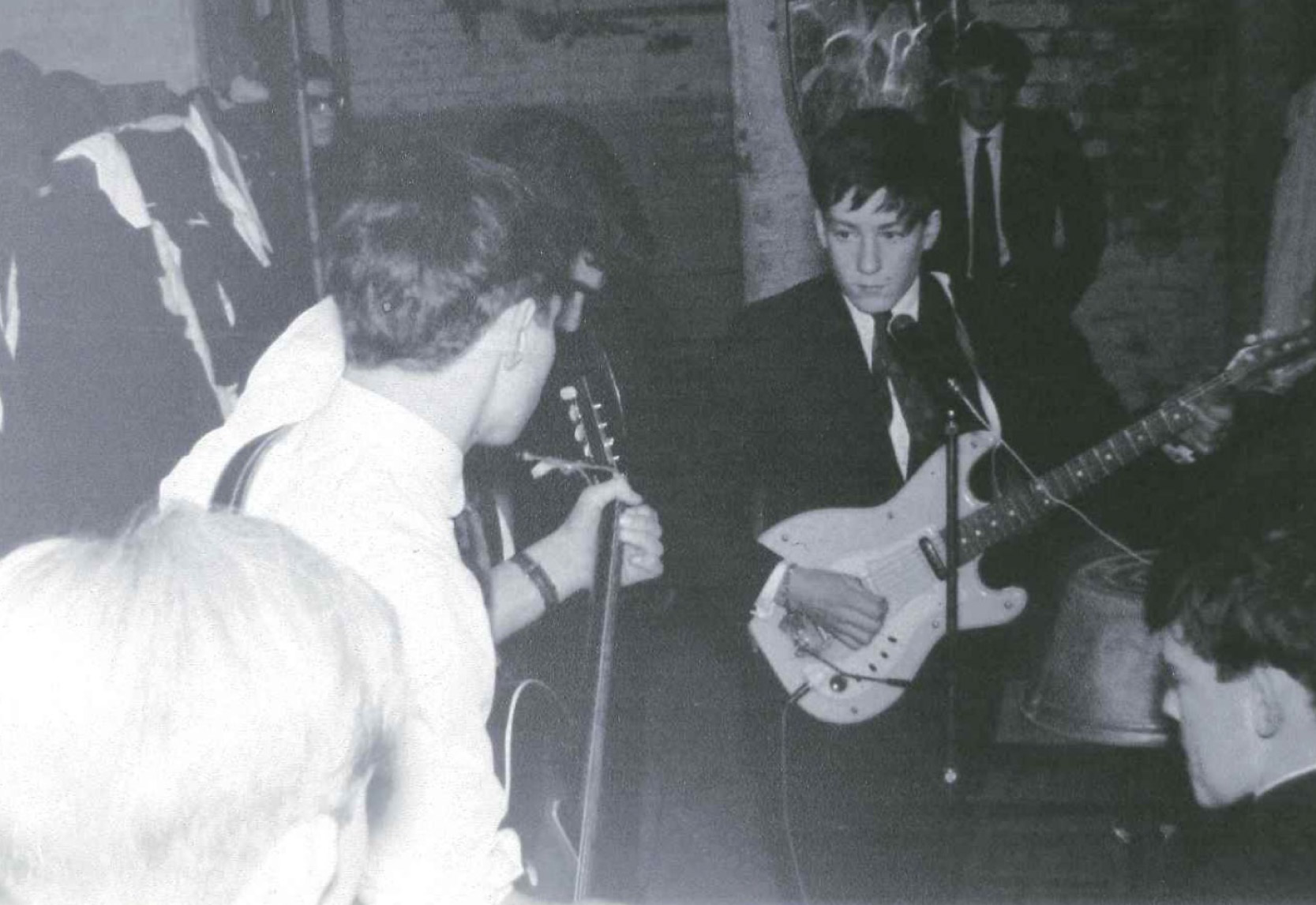

George & his brother's band

Childhood

George Fenton was born in Bromley, Kent in 1949. He was one of five siblings. His father was a mechanical engineer, and his mother had been a dancer and dance teacher before becoming a nurse during the war. Both his parents were musical – his mother played the piano and his father the drums – but weren’t musicians. However, his great grandfather on his father’s side was a conductor, and as a child had been a chorister and had sung at the funeral of the first Duke of Wellington. George sang in church choirs as a boy, but it was the electric guitar – a Rosetti Lucky 7 – that first won his heart at the age of 7.

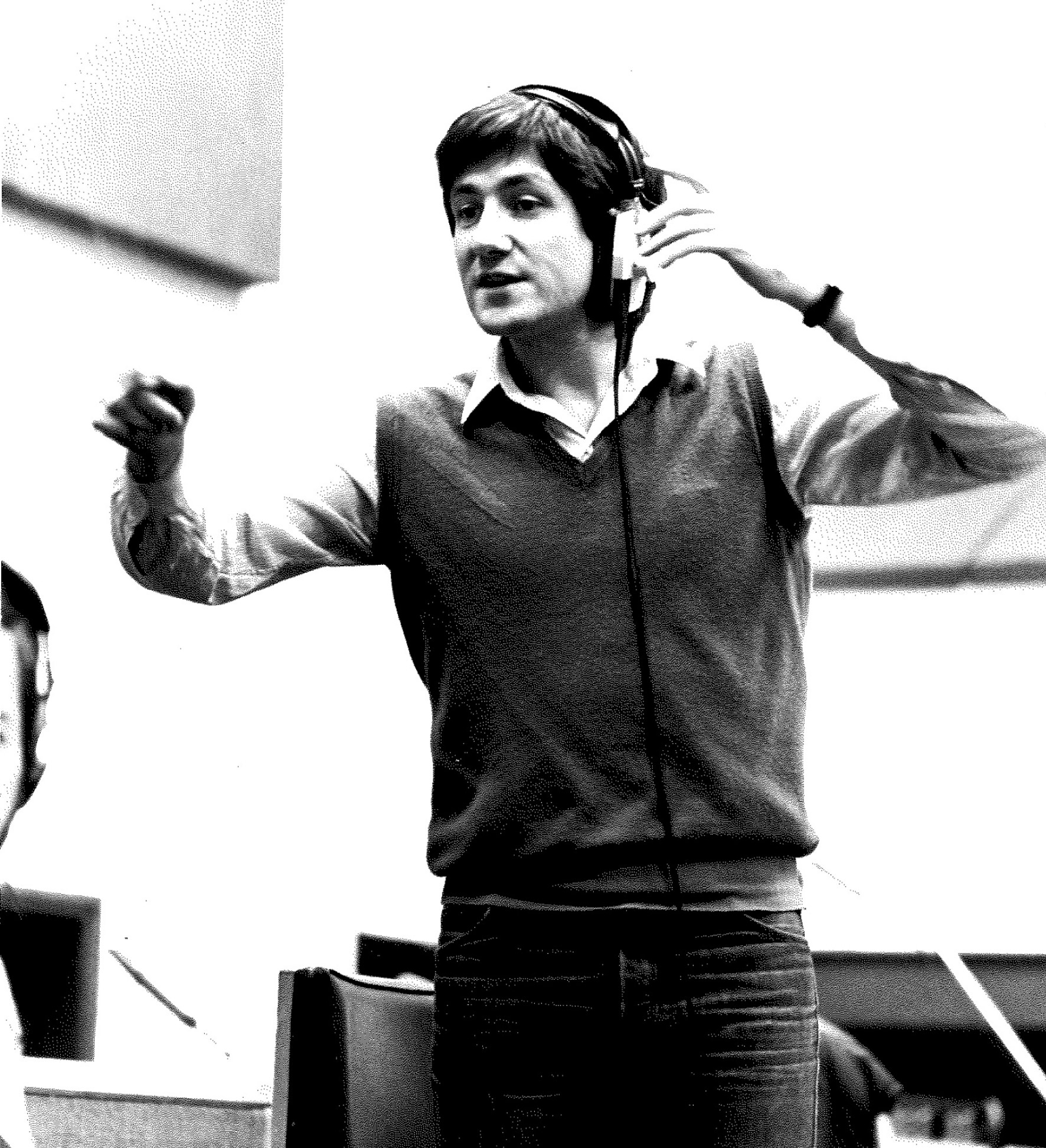

Peter Whitehouse

Education

At the age of 12, George began to study the church organ. This was a crucial part of his musical upbringing. Not because of the organ itself (although church music was to be a lasting influence on his writing), but because it was at this point that he was fortunate enough to encounter two exceptionally gifted musicians who would have a lasting influence on him. They were both former cathedral organists and worked at St Edward’s School in Oxford: David Pettit was the director of music, and Peter Whitehouse the assistant director. David Pettit went on to have an outstanding career as a performer and an academic. George credits Peter Whitehouse with being the most important person in his musical life, as a teacher and, ultimately, as a colleague. Peter continued to mentor and work with George until his death in 1992.

Acting

Having turned down the opportunity to go to university, George played in various bands and did a string of odd jobs until he auditioned for and was cast in Alan Bennett’s play, Forty Years On, in 1968. He also understudied the musical director of the show, Carl Davis. In order to appear onstage he had to join the actors union, Equity, and the rules prohibited two people having the same name. George was christened George Howe but because of this rule had to change it. That’s how he came to adopt his mother’s maiden name, Fenton.

John Leach

Music Career

While George was still in Forty Years On, he signed a record contract at MCA as a recording artist, and then one with his band at Decca. He worked as a session musician for some pop artists, including B. A. Robertson in the early days of his band. He also did some arranging for Carl Davis and others in theatre and television. He became increasingly interested in Middle and Far Eastern music thanks to meeting, studying, and working with the remarkable musician and ethnomusicologist John Leach.

Theatre

In 1974, George was asked by the director Peter Gill to write the music for Twelfth Night for the RSC in Stratford. Since then he has written extensively for theatre, television, and film. Reflecting his new role, he was one of the original group that founded the Association of Professional Composers in 1976, which later amalgamated with two other organisations to become the British Academy of Composers & Songwriters. His theatre composition work spans all of Peter Gill’s productions at Riverside Studios to Alan Bennett’s Hymn and Cocktail Sticks at the National Theatre. He also wrote the musical Mrs Henderson Presents, which was produced in the West End in 2016. George wrote the music for the BBC’s 2020 Talking Heads, both for television and at London’s Bridge Theatre. This was followed swiftly by ‘Beat The Devil’ with Ralph Fiennes, ‘Bach & Sons’ and ‘Straight Line Crazy’, also at The Bridge.

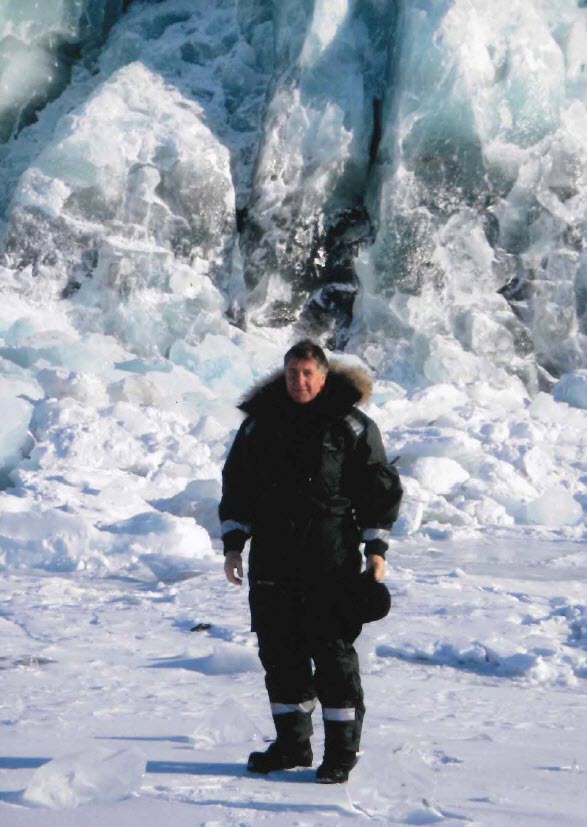

George in Arctic during the filming of Frozen Planet

Television and Documentaries

Whilst working in theatre, George began to write scores for television. His score for Stephen Poliakoff’s Hitting Town was the first of many TV adaptations he worked on. Throughout the ‘80s, he wrote the music for a variety of TV series, including the BAFTA-winning The Jewel in the Crown, The Monocled Mutineer, and Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads. He has also written many well-known themes for television, including BBC’s One O’Clock News, Six O’Clock News, Nine O’Clock News, Newsnight, The Money Programme, and the hit series Bergerac (another BAFTA winner).

In 1990, George scored his first natural history documentary series, David Attenborough’s The Trials of Life, and followed it up with Attenborough’s next series, Life in the Freezer. This led to the producer Alastair Fothergill asking George to compose the music for The Blue Planet in 2001, which began a 10-year period of writing for natural history television programmes, including Planet Earth, Frozen Planet and Life. In 2022 George partnered up with Alastair Fothergill and David Attenborough again, this time for BBC One’s Wild Isles series.

Film

As an indirect result of studying with John Leach, and as a direct result of his work at Riverside Studios, George was asked by Richard Attenborough to co-write the score to the 1982 bopic Gandhi with Ravi Shankar. He went on to score four more of Attenborough’s films. In fact, many of the films he has scored have been the result of long-lasting relationships with directors, such as Stephen Frears, Nora Ephron, and Ken Loach. Some collaborations are particularly prolific: he has written scores for Loach’s last 17 films, including Sorry We Missed You and the forthcoming The Old Oak which is in competition at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival. Other recent films include Cold Pursuit with Liam Neeson, Red Joan starring Judi Dench and Sophie Cookson, Andy Tennant’s The Secret: Dare To Dream, The United Way, Beat The Devil and The Duke and this year will so far bring ‘The United Way’, ‘Beat the Devil’ and ‘The Duke’.

This year has so far seen Alan Bennett’s Allelujah and awaits the aforementioned The Old Oak, and Andy Tennant’s thriller, Unit 234.

Just some of George’s other film credits include Cry Freedom, Shadowlands, Dangerous Liaisons, The Madness of King George, Memphis Belle, The Lady In The Van, Groundhog Day and so many more.

Hollywood Bowl Show 2002

Live

In 1990, George scored his first natural history documentary series, David Attenborough’s The Trials of Life, and followed it up with Attenborough’s next series, Life in the Freezer. This led to the producer Alastair Fothergill asking George to compose the music for The Blue Planet in 2001, which began a 10-year period of writing for natural history television programmes, including Planet Earth, Frozen Planet and Life. George went on to turn The Blue Planet score into the influential concert series, The Blue Planet Live!, in which an orchestra played live to sections of the cinematic footage. In 2003, he scored and conducted the music for the documentary film Deep Blue, which was performed by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra – the first film score the Orchestra had recorded in its history. In 2007, they repeated the collaboration for the documentary film, Earth. With the producer Jane Carter, George turned each of the scores into concert works. His live film scores continue to be performed by orchestras worldwide.

Awards

George began to be recognised for his scoring work in the 1980s, and received his first award at the BAFTAs in 1982 for ‘Best Original TV Music’ with Bergerac and The History Man. To date, George has won an impressive total of 28 awards for music composition including Baftas, Emmys, Ivor Novellos, BMIs and a Classic Brit Award, and he’s been nominated for a further 49 awards including Grammys, Academy Awards, Golden Globes and more Ivor Novellos.

Now

George Fenton lives in London. He is a BASCA Fellow which makes him just one of 18 songwriters and composers to have been bestowed this huge honour. He is also a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and is a visiting professor at the Royal College of Music and the University of Nottingham. He continues to compose for film, television, and theatre. Recent film and TV credits include Cold Pursuit, The Secret: Dare To Dream, the BBC’s Talking Heads series which was subsequently produced at London’s The Bridge Theatre., The Duke, Allelujah and BBC One’s Wild Isles narrated by David Attenborough..